Putting represents the sharp end of golf. Good putting can cover up a multitude of ball-striking sins and make a bad score okay, an okay score good, and a good score great. Bad putting, on the other hand, can do just the opposite.

There is nothing more frustrating than hitting a string of good drives and approach shots, then missing every putt. Putting, then, is a game within a game. The fact that you have a sound, on-plane full swing means nothing when you get on the greens.

Good putting requires a whole different technique. And this makes sense when you think about it.

Uniquely in golf, a well-struck putt stays on the ground all the time. And to achieve that you really don’t want to move your body at all.

A good stroke is one where you swing the club with your arms and shoulders. Every other swing involves at least a little body movement to get you through the shot with some rhythm and timing.

Still, in putting there are more ways of getting the job done effectively than in any other part of golf. The relative shortness of the stroke allows you much more flexibility in terms of method.

Indeed, putting is a test of feel, touch, and nerve as much as technique. If you don’t have those first three qualities, it really doesn’t matter how good your stroke is. That is why you can make putts using a variety of putting grips, many more screwy-looking setups, and certainly a lot of different putters.

Having said that, there are two distinct putting styles used by the vast majority of golfers.

- There is the open-to-closed “swinging gate” method used by, among others, Ben Crenshaw.

- Then there is the more straight- back, straight-through stroke.The vast majority of players on theprofessional tours favor that approach.

And I must admit I share their preference. I like straight back-straight through, the face square to the line from start to finish. It’s simpler. But each method has its own distinct characteristics.

Table of Contents

1. How To Putt Using ‘Open-to-Closed Technique’

From address to the end of the follow-through the putter stays close to the ground. The putter face opens on the backswing, then closes on the through swing. In that respect it is almost like a miniature full swing, although the arc it follows is, of course, flat.

Generally, this stroke is long and flowing. You need good tempo to make it work effectively. There should be a smooth, rather than easily discernible, acceleration of the blade through impact.

For that reason, open-to-closed putters are usually above average lag putters. As you’d expect, because the face of the club is square to the target for only a short length of time, the position of the ball within the stance is crucial.

There is no margin for error as far as moving the ball forward or back is concerned. Too far back and you will tend to push the putt to the right; too far forward and you will tend to pull the ball to the left.

You’ll probably feel more comfortable with a fairly upright posture, your arms hanging almost straight down. That makes it easy for you to make the stroke with your arms and shoulders.

There should be virtually no wrist action. If you favor this style of putting, you will find it easier to achieve with a heel-shafted putter. It will allow you to stand tall and away from the ball. The clubface rotates around the shaft, accommodating the open-to- closed shape of the stroke.

2. Straight Back-Straight Through Technique

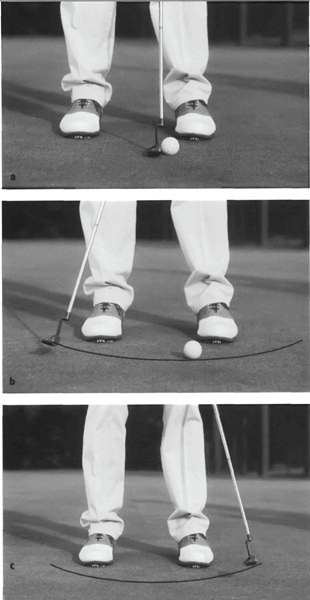

This method typically involves a shorter and more “up-down-up” type of stroke.

That gives you more leniency in terms of where the ball should be within your feet. Really, it can be anywhere from opposite your left big toe if your left eye is set up overthe ball, to the center of your stance if your head is set up behind the ball.

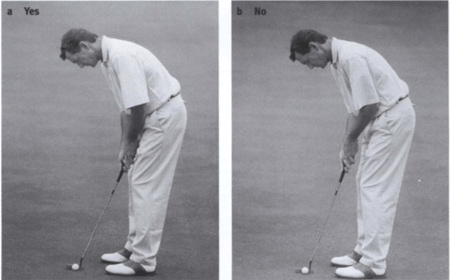

Where there must be no doubt is in how far you stand from the ball. It is a great advantage if your eye-line is directly over the target-line. In fact, this is the only shot in golf where it is possible for you to look directly down the target-line. To achieve that you will probably have to bend over more from the waist.

Think “up a little (a) … down a little (b) … up a little” (c).

Move the putter back and forth by rocking your shoulders, straight back and straight through. There should be no feeling of the clubhead moving inside or outside the target-line at any point during the stroke.

Use a center-shafted or face-balanced putter for this method. Having the shaft more toward the middle of the blade gets your head more over the ball, and encourages the straightness you want in your stroke and the squareness you want in the putter-face.

Take note, however. On really long putts, no matter what your technique, you are going to have a stroke that has some arc to it.

Eventually, the clubhead just has to move inside the line. But as far as your thoughts and feelings are concerned, change nothing. Just let it happen.

Loft

Whatever putting style you end up favoring, don’t forget the importance of loft on your putter. Yes, loft. Believe it or not, putters generally have anywhere from three to seven degrees of loft.

Depending on the greens or your style of putting, you might need a putter with a different amount of loft. In general, the tighter the greens are cut, the less loft you want.

The shaggier or grainier the greens are, the more loft you want. More loft helps you get the ball rolling on top of the grass. Factor in your putting style. Maybe you like your hands farther forward at address. If so, you need more loft.

You are, in effect, delofting the club with this hand position. If you like your hands back more, you want less loft on your putter.

Arms and Shoulders

Again, this is my preference. I like to see my pupils putting with the arms and shoulders. I like to see them maintain the triangle formed by their arms and shoulders from address to post-impact.

That is the technique employed by most of the best putters on tour. But there are other ways. Billy Casper, one of the greatest putters ever, had a very wristy, “pop” type stroke. So I can’t in all honesty say that using yourhands in the stroke is necessarily wrong.

But less hands is better if you’re struggling. Also, always make sure your wrists are in a relaxed position and not arched up at address or during your stroke. If that happens it is difficult to keep a consistent stroke where the face and path stays square throughout the stroke.

Your wrists should be relaxed when you address a putt (a), not arched (b).

The Grip

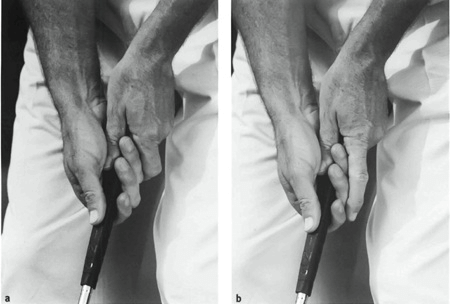

Most professionals use the reverse overlap grip for putting. The idea is that it helps eliminate wrist action from the stroke.

In it, the forefinger of your left hand overlaps the little finger of your right hand. Or the forefinger extends down over all four fingers. That tends to keep your hands out of the stroke and keep your wrists firm, which is what I advocate on putting.

While it is a personal thing, I like to see both thumbs going straight down the shaft. And both palms facing and perpendicular to the target- line. But, again, you can hold the club any way you want to within reason. If it works, of course!

In a reverse overlap putting grip, your left forefinger can overlap (a) or extend (b).

Distance

How far you hit your putts is a much underrated aspect of putting. No one seems to pay much attention to distance-control, so it’s no surprise that it is the biggest weakness I see in amateurs.

Realize that if you don’t hit every putt solid, your feel will constantly have to adjust to the vagaries of your stroke. For example, if you hit the ball off the toe of the putter it won’t go far enough. Do that long enough and frustration inevitably sets in.

So all of a sudden you hit the next putt harder and catch it solid—and it runs ten feet past. All because you’re not hitting your shot consistently solid. Once you can hit your putts solidly on a regular basis your focus needs to be on the speed of your putts.

Think of it this way. On every putt there is an optimum distance the ball should roll past the hole. The distance you hit the ball determines your percentage of possible makes.

Dave Pelz did a test with a machine rolling ten foot putts which barely reached the hole. The machine made only about 50 percent of those putts. That percentage went up to about 90 when the speed on the ball was increased to where the putt would roll seventeen inches past the cup.

The conclusion is obvious. You’ll make more putts if you hit them at a pace which would see the ball come to a halt about a foot or so past the hole. At least on relatively flat putts. Seventeen inches can turn into three feet pretty quick on a downhill or sidehill putt.

Those putts are lag putts. Aim for the front lip on those. But, generally speaking, putts need a little pace on them to hold the ball on line. If you “die” a ball at the hole, it will be moving slowly and be more susceptible to any imperfections in the green.

How much pace you give a putt depends on your situation and how good you are at controlling your speed. If you’re not very good, roll the ball to the hole and no further. If you’re good, roll your putts so that if they miss they will finish by the hole.

Reading the Breaks

When you have determined how hard you want to hit a putt, that calculation also determines where you should aim.

Every holed putt is a combination of perfect pace and perfect line.

You need to get both pace and line correct if you want to make a putt. I see amateurs spending a lot of time on the greens trying to figure out how much putts are going to break. Then they hardly consider how hard they are going to hit the ball.

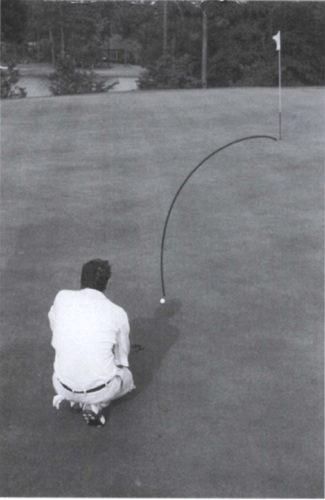

How much break you play is always related to how hard you hit a putt. The harder you hit the ball, the less it will break.

The softer you roll the ball, the more break you have to allow. As a general rule, most golfers don’t play enough break. Statistics say that around 85 percent of all putts are missed on the low side of the hole and, for once, I believe the numbers.

You need to play four to six times more break than you think. That sounds like a lot, but it is a fact. Next time you are over a breaking putt consider that, even though you think you are playing enough borrow, so did 85 percent of the people who had this putt before you.

And they missed it low. So play more than you think! Try to beat the odds. You have a better chance of making it from the high side than the low.

The ball won’t drop in from below the hole. That’s why the low side is called the amateur side.

The more break you play, the better you are going to do with yourspeed. During the 1995 Masters Tournament CBS announcer Peter Kostis made a great observation on how Ben Crenshaw was handling the fast greens at Augusta.

He commented that Ben always plays the maximum amount of break on his putts. Allowing for the maximum break forces you to focus on your speed. Crenshaw does both and no one could deny that he has made his share of putts over the years.

Whenever you aren’t playing enough break you will instinctively hit the ball harder to keep it on line. That’s when the ball can get away from you. On fast greens especially, always play the maximum amount of break. That way, you can hit your putts as softly as possible.

Speed also determines how long your next putt will be. There is nearly always a next putt. No one makes everything. So you have to stand overevery putt considering at least a little bit your next putt. That’s not negative, just realistic.

Dare yourself to play enough break. Putts either break a little bit, or a lot. But always more than you think. And every green has some slope to it, at least a half inch for every ten feet.

That’s the way architects design putting surfaces so that they drain properly. There is no such thing as a flat putt. You may have a straight putt, but if so it is uphill or downhill. If you are standing on a perfectly flat green, you are standing on a dead green.

The best way to read a green is to look for where the water drains off it. Sometimes it’ll be off the front, sometimes off the side, sometimes off the back. Greens are designed to get water flowing off of them. If you dumped a big bucket of water on the green, where would it go? That’s where the ball goes, too.

Make Every Putt Straight

Let’s pause for a moment. The last few paragraphs will have hopefully made you think more about your putting. Which is good. But don’t go too far. Don’t go thinking that putting is a complicated and difficult process. It isn’t. Keep things simple.

For example, you don’t “work” the ball in putting. You can’t hit hooks and slices. So every putt is essentially straight, no matter how much break there may be. Think about it. Even if you have a thirty-foot putt with a six-foot break on it, you still have to pick a point where you want the ball to start.

You don’t have to worry about the borrow, only your “target.” Pick your breaking point and start the ball there. Focus only on that. Let density do the rest for you.

Pre-Shot Routine

Just as in the full swing, a consistent pre-putt routine can instill a feeling of comfort and confidence once you are over the ball. “Sameness” is good. Approach the ball from behind. Visualize the roll of the ball over the green, all the way to your aiming point.

Then set your putter down, placing your feet perpendicular to the line. An open stance is also okay. Bobby Locke, one of the greatest putters ever, stood closed. But I like the orthodoxy of a square stance. If you are looking for consistency, it is nearly always best. Reinventing the game can be risky. Keep it simple.